More than fifty years ago, my three-year-old son David and I went grocery shopping in our smallish neighborhood supermarket. I concentrated on the week’s bargains while he immersed himself in the comics rack. Suddenly I felt a small hand tugging at me. When I turned, I encountered David’s terror-struck face. He had been unable to find me and was convinced that I had lost him for good. Reassurance, and some guilt on my part, followed. I realized how scary the world was for David.

I can imagine the terror that enveloped the children at the US-Mexico border, and the grief and horror experienced by their mothers and fathers. It is hard to kiss small children goodbye when they first leave us to attend daycare, elementary school, or sleep-away camp. These, however, are necessary life-changes. Having one’s child wrested from one’s arms by a stranger represents a trauma of epic proportions. And of course, there is bitter irony in the fact that many parents have undertaken this journey precisely in order to provide their young with a brighter future.

When Trump’s latest strategy to eliminate undocumented immigration became public, so many US citizens protested that the president rescinded his original order and stopped separating parents and children at the US-Mexico border. But much damage had already been done. As of July 1, 2018, approximately two thousand children were still separated from their parents and the prospect of their timely reunion were dim. Some officials fear that some of the separated children will end up being “immigration orphans.” Jeff Sessions has offered the following as justification: “If people don’t want to be separated from their children, they should not bring them with them.”

I can visualize and identify with the chaos that reigns at the US’s southern border. I especially identify with the teenagers. Seventy-eight years ago I too camped in front of an impregnable border. On May 10, 1940, the Germans invaded Belgium. Five days later my mother, my little sister and I tried to cross the Belgian-French border near Dunkirk. We were refused admission because we did not have the correct documents. We were running away from the German army and trying to join my father in France, who had been arrested as an enemy alien (I would not see him for six years). We did not manage to cross the border but tried repeatedly during the next three days. In between attempts we camped in the sand dunes. I can’t remember what we did for food or how we attended to our other bodily functions. Eventually we all retreated and returned to the Belgian capital, where we miraculously survived four years of German occupation.

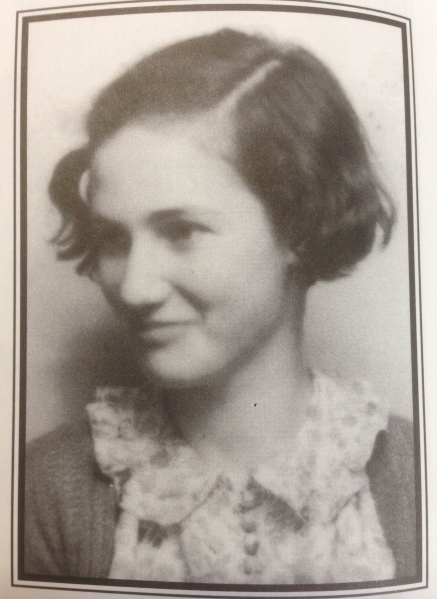

Elizabeth Wolff

During this fruitless expedition, when one million Belgians tried to escape the Nazis, I happen to run into Elizabeth Wolff, my best friend. Her family too was trying to escape the German army. Elizabeth is a prime example of the emotional damage that world history inflicts on the innocent, and her abrupt separation from her parents was part of her root problem.

During the late 1930s, when the fate of many European Jews hung in the balance, the Refugee Children’s Movement rescued Jewish children by having some free European countries waive their residence requirements. This so-called Kindertransport (“children’s transport”) operation was a wonderful but heart-wrenching program that saved more than 10,000 children. Elizabeth had kissed her parents goodbye at the Berlin railroad station without knowing who would care for her in Brussels. The Hollenders, the kind parents of three older daughters, adopted her until she would hopefully be reunited with her own parents.

I met Elizabeth during recess at our local high school soon after she arrived. We rapidly grew very close. We visited back and forth and talked incessantly about sex, politics, our teachers, my irascible mother, the Hollenders and Elizabeth’s parents. At first Elizabeth heard from them regularly. Then the letters grew sparse, and finally they stopped. They were murdered. In 1942, both the Jewish Hollenders and my family went into hiding until 1944. I missed my friend dreadfully. I could not wait until the war was over and we could resume our friendship.

When that happened, Elizabeth had changed. We saw each other rarely, then I moved to America. I knew that she became a nurse, married a doctor, and had three children, who happened to be same the age as mine. In 2000, after I had written my wartime memoir At the Mercy of Strangers, which chronicled our friendship, I went to visit her in Belgium. To my utter surprise she seemed to have forgotten all about me. She apologized and wanted to know how the two of us had met. It appeared that she had erased most of her past. Her husband and children had been instructed not to talk to her about the Holocaust, and her friends believed that the Hollenders were her birth parents.

Surprisingly, she slowly rekindled our friendship, whose loss had caused me so much grief. Elizabeth recovered her knowledge of German and other long-lost memories. She died in 2015. I miss the years of friendship we could have had.

I am reminded of Elizabeth when I look at the children now in custody at the US-Mexico border. Will they ever recover from the trauma they have experienced?

I an also sympathize with those separated children. I was 13 years old when my parents took me to the Westbahnhof in Vienna and sent me, all alone, to America to be cared for by a non-willing great aunt.They gave me $10 !!!! I somehow survived. Nelly Ullman

Such a moving, insightful, and timely piece.

Thank you, as always, for your perspective on the world.