Picasso tapestries in the underground art galleries at Kykuit. (Photo © Jaime Martorano)

On the cusp of summer, the French Institute Alliance Française—one of New York’s oldest institutions, bonding the United States and France—invited Mary Louise Pierson to talk about the lavishly illustrated book she and her mother, Ann Rockefeller Roberts, published about her family’s weekend home in Pocantico Hills, NY. Mary Louise, a graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design, took the book’s intimate pictures; Ann Roberts Rockefeller provided the lively text. The book, published by Abbeville Press, is called Kykuit: The Rockefeller Family Home. I attended the lunch because the talk would remind me of the five years I spent researching and writing about the Rockefellers’ contributions to the American art world.

In 1893, soon after the center of his oil business shifted from Cleveland to New York City, patriarch John D. Rockefeller, Sr. bought the land on which the estate rests. For a while the senior Rockefellers lived in a house that came with the estate, but in 1902 his son, known as Junior, built an imposing Beaux Arts mansion for his parents. The house is located atop and named for Kykuit (Dutch for “lookout”), a hill that dominates its surroundings. Indeed, from certain vantage points, the visitor is awed by a view of the mighty Hudson.

The house is designed for summer living; the gardens that surround it are truly magnificent. Today Kykuit is a house-museum shaped by three generations of Rockefellers. Senior equipped it with an organ and a golf-course; Junior —whose favorite architect William Welles Bosworth, designed the gardens—gave it its regal character; and Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller, the last live-in Rockefeller, provided it with its final form. He removed the organ and also endowed it with a major 20th century sculpture collection. Nelson was Ann Rockefeller Roberts’ father and Mary-Louise’s grandfather,

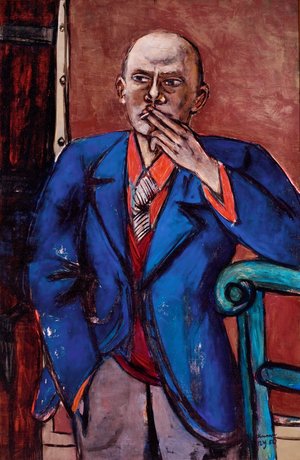

During her presentation at FI:AF, Mary Louise emphasized her loving relationship with her grandfather and entertained the audience with personal stories. Assisted by MoMA’s René d’Harnoncourt, Nelson spent much time arranging his sculptures in their ideal location. One of Mary Louise’s stories involved a brotherly disagreement between David and Nelson Rockefeller on the subject of the noise and disturbance caused by a helicopter as it repeatedly adjusted the placement of a large Henry Moore sculpture while David played golf with important Chase Bank clients. Today Nelson’s sculpture garden, which includes works by Aristide Maillol, Pablo Picasso, Jacques Lipchitz, Gaston Lachaise, Elie Nadelman, Alberto Giacometti and many more, is one of the finest in America.

I identified with Mary Louise’s pleasure at photographing and illustrating Kykuit. I visited the estate repeatedly, and as well as most of the 37 other institutions that benefited from the Rockefeller’s financial largesse, hard work, and excellent taste, all recorded in my latest book, America’s Medicis: The Rockefellers and their Astonishing Cultural Legacy (HarperCollins). It was so much fun creating that book that I wish that I could do it all over again.

The elegant lunch provided by FI:AF matched the refinement of Kykuit. Each one of the dozen or so tables was napped by bright-blue tablecloths and highlighted by vases of tulips and shiny, stemmed wine glasses. The food was equally delicious, and the festivity of the penthouse space at 22 East 60th Street matched the excitement of the afternoon.